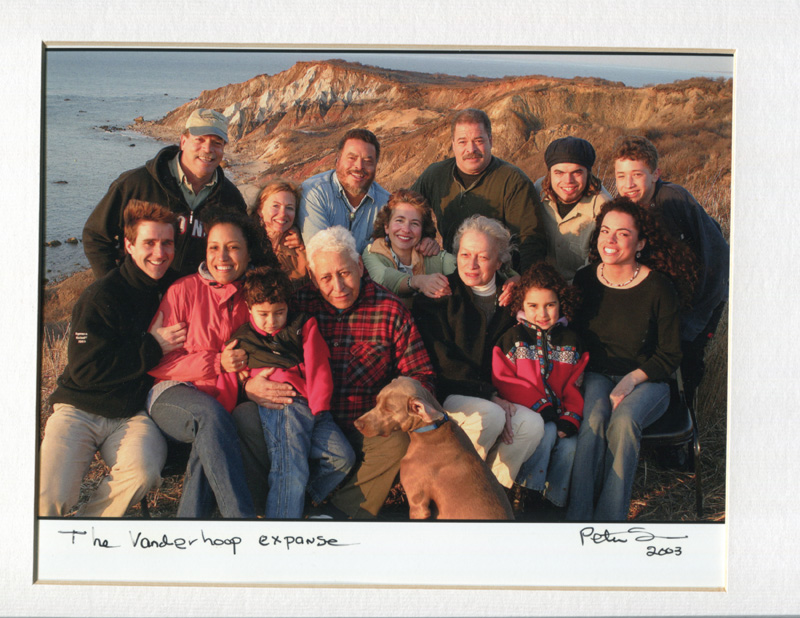

Tina Miller and I sat down with Juli Vanderhoop and her mother Anne Vanderhoop on a sunny fall afternoon to hear their food story — baking pies, passing recipes and food traditions down. As most know, Juli has run the Orange Peel Bakery in Aquinnah for more than 14 years. And Anne has been making and selling her pies since the late ’40s. As we got settled on the Orange Peel Bakery’s porch, Anne’s opening comment — “The world is as strange as I’ve ever seen” — tipped us off that our conversation might hold more than a pie.

But first, let’s start with how it all began, back in the early 1940s. “Napoleon Madison had a tiny stand up at the Cliffs. Soda in an old-fashioned Coke cooler. Coffee. Hot dogs and hamburgers. He had one of those old-fashioned gas grills where the coffee was on one side, and he’d cook on the other. Nellie Amaral, who drove a taxi, would bring people up to the Cliffs and they’d have a bite to eat,” Anne explains.

“He served the coffee with canned, evaporated milk,” Juli adds, laughing.

“Yes, I said to him, ‘You can’t serve that in that tiny beer mug.’ But Uncle ‘Poley’ did. He said, ‘Yes I can,’” Anne says with a smile. “He invited me up to work. It gave us a little extra. I had seven children. Six boys and my little treasure,” Anne says as she pats Julie on her thigh.

The short version of the story goes that Napoleon’s customers eventually wanted more than burgers and pie. So Anne began baking cookies as well. Then he asked if she could stay a little longer to help out. His roadside stand business grew a little bigger, and over four generations, became the iconic Aquinnah Shop.

Tina asks Anne, “Who taught you to cook? Your mom?”

“My mother didn’t allow me in the kitchen. She was a cook and a housekeeper. I guess I taught myself.” Anne pauses and then explains more: “She wasn’t my biological mother. I never knew my mother [or father]. They didn’t do all that formal adoption stuff in those days. I was born in 1931. Gertrude Williams took me, a biracial baby, in and raised me. She was tough. I grew up in Providence. We lived on Camp Street near Doyle Avenue. She worked for families along Blackstone Boulevard. We would come here to Edgartown in the summer and work for them. She’d cook and do housekeeping, and I’d babysit.”

I also grew up in Providence, and can tell you that Blackstone Boulevard was and is, as it sounds, a fancy neighborhood filled with large houses, big trees, and vibrant green lawns. It turns out that Anne also went to Hope High School, which was one block away from my childhood home.

“I did well in school,” Anne says. “I had graduated, and was all set to go to the Wilson School of Technology to become a lab technician. I had paid and everything. But then the worst thing ever in my life happened.”

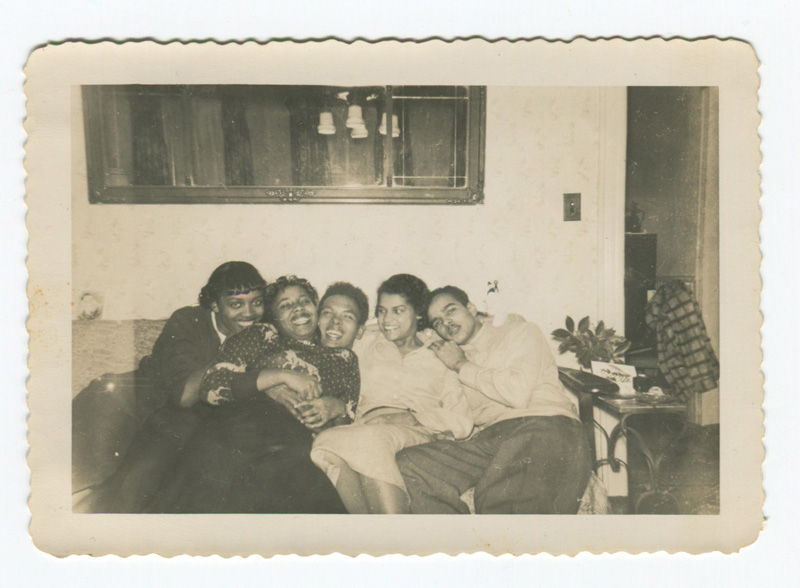

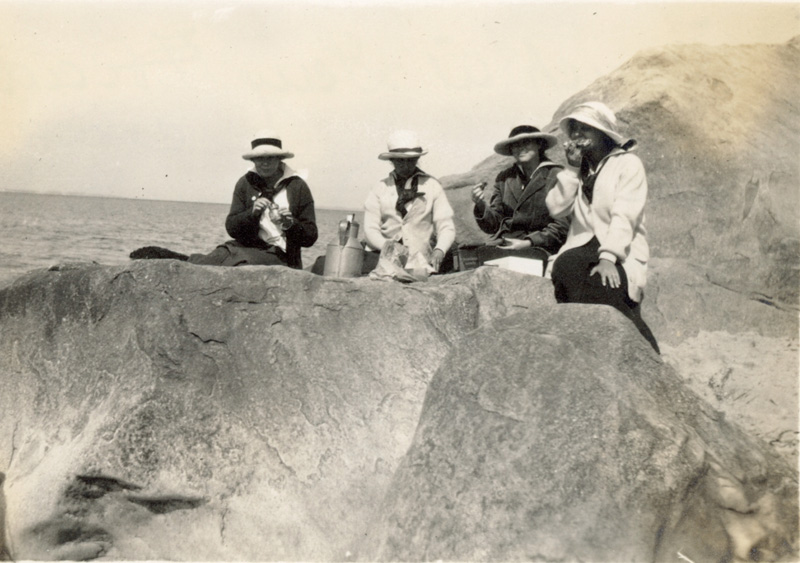

Anne backs us up in time, and tells us about the Open Door Club, which was at the corner of Cooke Street and Tilton Way in Edgartown. The Open Door Club was founded by Edna Smith and Louise Harper in 1939 as a kind of refuge for black household help — it was a place where “the help” could come cook, hang out, and rest on their days off. During the summers, the Open Door Club would host picnic gatherings at 3 Mile Beach. Everyone would bring food. “It was delicious,” Anne says. It was at one of the beach picnics that Anne met William Vanderhoop.

“And if you put out a big feast anywhere, the Vanderhoops will show up. It’s just a fact,” Juli adds, laughing.

Anne nods, “That’s true.”

One of her summer friends, Ann Mouche, was from New York. “She was a pretty girl,” Anne remembers. “She was Candy, and I was Cookie.” And the summer after Anne graduated from high school, Ann Mouche asked Anne to come visit her and see the city. “But I was going to college. So I headed back home to get ready. My mom was very strict. On my high school graduation night, a boy I was seeing put a ruby and diamond ring on my finger. My mother nearly wrenched my finger off, saying, ‘Give it back.’ I wasn’t allowed to go many places. Maybe the park. We walked everywhere. She didn’t have a driver’s license.”

So one can imagine Anne’s mother’s reaction when three Vineyard boys showed up at their Providence doorstep, asking if Anne could take a drive with them to see Ann Mouche in New York City. “Lucy, my friend from Providence, also wanted to go. But her mother was as strict as mine. So we lied and asked if she could spend the night, studying at my house. And for some reason, her mom, who never let her out of her sight, said, ‘Yes.’ So did my mom. That was a shock.”

Mothers convinced, the three boys, Lucy, and Anne took off for the big city. Somewhere in Connecticut, Lucy, who had been in the middle seat, asked if Anne could switch with her. She did. Shortly after that, in the dark night, they drove head-on and full speed into a tractor-trailer truck that had broken down in the middle of the road on the highway. Lucy was killed. Anne nearly lost her right leg. It took her six months to recuperate. And Anne still walks with a limp.

“I woke up and wished it had been me. That lie we told. That life loss. It never leaves you. My life was forever changed,” Anne says.

Because of her injuries, Anne couldn’t go to school. Her mom wanted her to get married to William Vanderhoop. “She loved him more than I did,” she says. So in 1949, Anne married William Vanderhoop and moved to Aquinnah, and had seven children: Buddy, Ricky, David, Todd (Todd passed away when he was just 2 years, 3 months old), Cully, Chip, and Juli. “And, as you know, they are not small children. We used to get nine gallons of milk a week for those kids.”

William and Anne divorced in 1970. About 10 years later, Anne married Luther Madison.

“I used to make the crust, and he would do the fillings,” Anne says about their pies.

“The last 16 years of his life, Luther was sick,” Juli says, describing how during his illness, Anne and Luther’s pie-making routine changed. “They told him he had two months. But he’d make pies every day and lived for 16 more years. When he wasn’t feeling well, he’d roll out of bed and make the crust. Then go back to bed. Then he’d get up to fill the pies. Then back to bed. Then up to put the lid on. Back to bed. Up to bake the pies. Back to bed. It was his meditation. Watching this process, I fell in love with food and the oven. The smell. There is so much joy in food. It can be an inward process or out. When I had kids, I didn’t want my kids to eat junk. So I started baking for them. Everything we do here at the bakery is handmade.”

“Everything used to be handmade here [on the Island]. Our house was built by one man, Dan Belain,” Anne says. “Now there is a specific person for every part of a house.”

Juli’s son Emerson, who just graduated from Dartmouth College, pops out of the house in a dashing bright blue suit and white sneakers. Juli looks at him and says, “Hey, Bruno Mars.” And then explains that he’s going to photograph a wedding for a friend.

Are Juli’s kids cooking? She shakes her head. “Emerson? No. He’s doing videography. Ella [her daughter] is an artist in Brooklyn. But everyone in the family has worked at the Aquinnah Shop.”

Anne nods in agreement, “Everyone. Even though they’d all rather be playing basketball every day of their lives.”

As we talk, Orange Peel customers shuffle in and out, each of them finding an excuse to talk to Juli or greet Anne. “Nancy Aronie called to say that she had to come back and get another pie. She ate the first one before Joel could have any,” Juli says, laughing. “My mom always says, Make it good so you don’t have to advertise.”

This spring Juli expanded her business, as she has said in an interview with The MV Times: “Move as much food to the people as I possibly can.” She created a virtual up-Island grocery, filling up entire 18-wheelers to the gills with cheeses, milk, juice, paper towels. The whole gamut. Outermost Inn proprietor, friend, and neighbor Alex Taylor helped set up the pricing. “We want people to be healthy. When we pass food, community comes.”

“I have made so many friends,” Anne agrees.

“Coming to Aquinnah is an effort. But our land is magnificent. Maybe a little spooky sometimes,” Juli laughs. “I want people to come here and eat from the ground. To know that their food comes from under their feet.”

Anne looks at her daughter and smiles with pride. Then it’s time for Anne to go home. Juli has to make more cookies. More food to come.