If you left Lynne Irons alone in the woods for a long weekend to fend for herself, by the time you picked her up to bring her home, she would have likely killed a half-dozen squirrels and cooked them up over a crackling fire, gathered her own rainwater to drink, and picked wild berries for dessert. She’s self-sufficient.

Lynne’s home in Tisbury is stacked to the ceiling with canning jars full of string beans, sauerkraut, tomato sauce, pickled beets, onions, squash, and every other vegetable you can think of, not to mention the jars of water everywhere. When we visited, there were bushel baskets and milk crates filled with apples covering the kitchen floor — she was gearing up to make cider.

“I hate wasting food. I grew up in Appalachia and we didn’t waste anything,” Lynne says. “I can’t get out of that. I never throw food away.” What she doesn’t eat, she gives away, and table scraps go into the compost bin where they will eventually become fertilizer.

She has chickens, Cornish game hens, a couple of pigs, a rooster or two, and a lame Island turkey who takes care of her own chicks and a couple more left behind when their mother took off. When the game is the right size to eat, she has no qualms about killing it and then serving it up at her kitchen table. She says she is the opposite of a vegetarian.

“I feel like if I’m going to eat it, I better have the nerve to kill it,” she told us as we sat down for a cup of tea. (We had to keep reminding her to slow down long enough so that we could take a photo of her.)

Lynne finds a way to use every part of the food she grows, and says she hates the idea of wasting anything — food, water, or anything else. Glass bottles of varying sizes, shapes, and colors sit on her countertop, ready to catch the tap water every time it runs in between washing and rinsing the dishes.

Wasting water is one of her pet peeves. There were a couple of instances when she decided she’d better can her own water in case disaster strikes.

“In 1986 when Chernobyl went off, I worried that radioactive materials would come around the world and pollute our wells, so I canned all that water. I boiled water, put it in the jars and put it into the pressure cooker and sealed it in there forever. I told my kids they could serve it at my funeral. I have a thing about water … we grew up without a steady source of drinking water.”

In Rew, Pa., where she lived, Lynne’s grandmother and mother both canned but she didn’t think much about it when she was growing up. Lynne, who came to the Island in the 70s, started canning her own food about 50 years ago with her best friend Sharlee Livingston. They had young children and babies when they first attempted to make homemade applesauce and preserve it.

“We made a million mistakes,” Lynn said. “We had the bright idea to put apples in the pressure cooker, we’d cook them up and run them through a sieve. Well, we couldn’t get the top off the pressure cooker, we had 10 pounds of pressure on it and the top blew off and went flying across the room, and I was holding a newborn. We scraped two quarts of applesauce off the ceiling. Never cook apples in a pressure cooker, the skin of the apples goes over the valve. That’s when we said we need to pay attention and we never had another accident. I have to say what I like is that we didn’t give up. We said, okay, we did something wrong but we went ahead and persisted.”

Lynne told us she only uses the pressure cooker for foods with low acidity; for everything else she uses a water bath. Her dilly beans recipe is published every year in her garden column in the Vineyard Gazette, which she’s written since 2007. Her kids would eat a quart of them with every meal, she said.

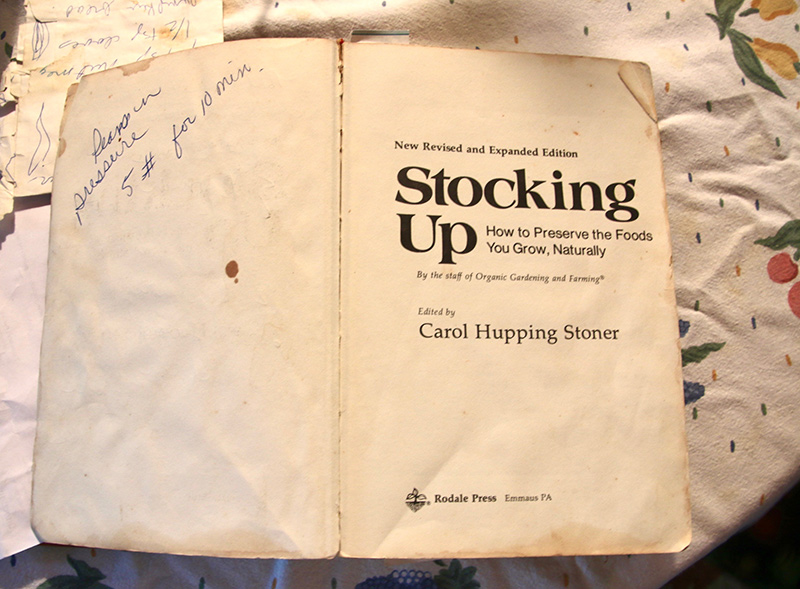

Lynne has a copy of the first edition of “Stocking Up: How to Preserve the Foods You Grow Naturally,” and she has used it as a sort of canning bible over the years. “This book tells you how to kill a chicken and how to store food underground,” she tells us as we take a look at her worn copy. “It’s the same book I’ve used for 40 years. It’s from the 70s and it’s where I get all my recipes.”

She grows her own food year-round and runs a gardening business most of the year. Food — growing it, preserving it, and eating it — is her passion. “There’s no saving in farming,” she says. “Every egg I eat is about 10 dollars when you count how much money I’ve spent. I don’t do this to save money. I’ve spent every penny I have doing this and the only thing I have to show for it is moral high ground. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, and I don’t get my hair done. I don’t go to big box stores. I don’t need a thousand Q-tips.”

Living simply is her credo, and after spending an hour with Lynne, you wonder why you aren’t doing it yourself, except you realize that she never sits still. “I just really like growing food,” she says, “and I can’t sell it. I give it away. If I sold it, it would make me anxious. I’d be afraid they’d leave it in the back of the refrigerator and it would go to waste.”