It all began with a cannon. A nine-inch muzzle-loading Dahlgren cannon that weighed nearly 10,000 pounds, to be precise. Captain Bob Douglas, founder of the Black Dog Tavern, spotted the cannon at the Boston Navy Yard, and decided he had to have it to add to his collection of marine memorabilia. “A nine-inch Dahlgren is very unusual,” Captain Douglas told me. “There are very few of those cannons around. This one was from the steam frigate Wabash, and it was built in 1855.”

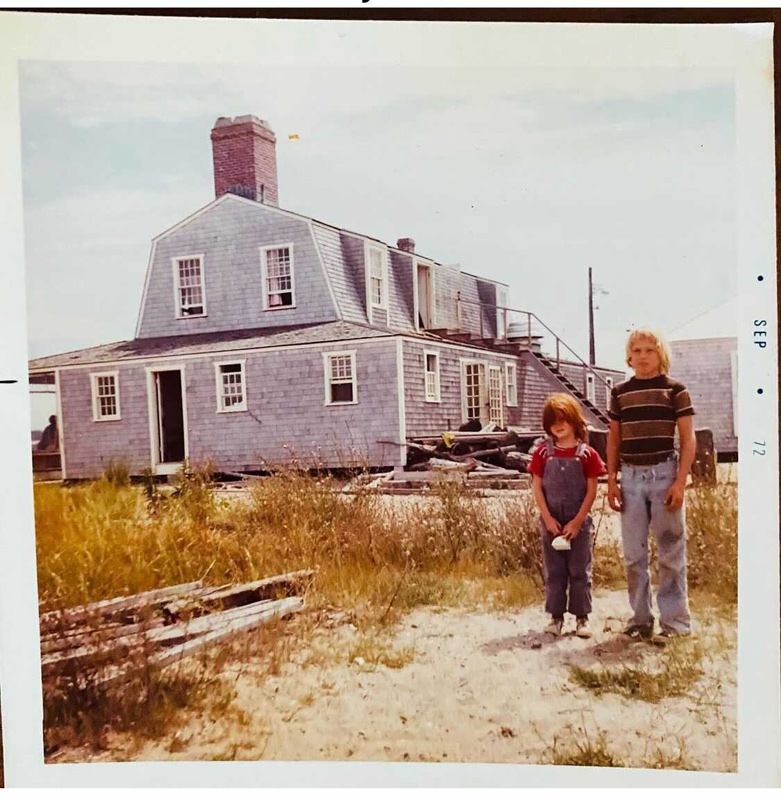

The cannon had been claimed by a salvage company on the South Shore, and they told Douglas that they could deliver it to Martha’s Vineyard, except that the truck they needed to use was already loaded with 6,000 pounds of yellow pine. Douglas agreed to buy the pine, thinking he could perhaps use it on his ship, the Shenandoah, and so purchased both the wood and the cannon, and had them delivered to the lot behind where the Black Dog Tavern stands today.

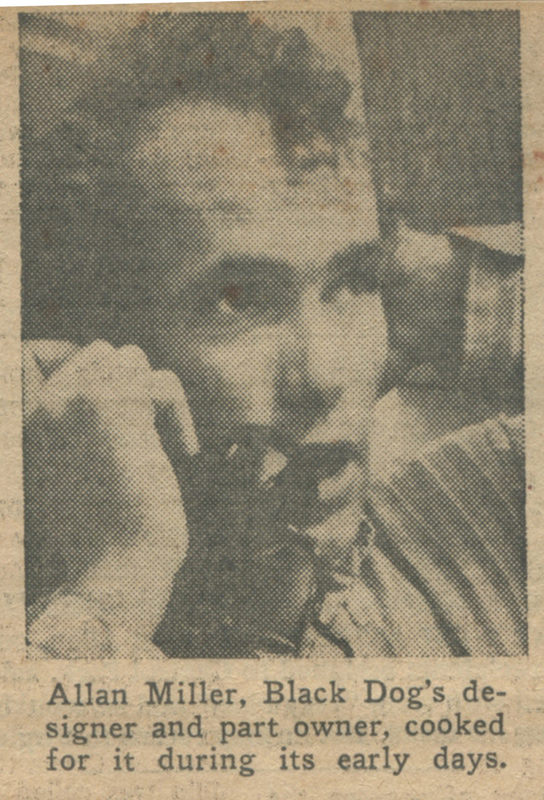

“The yellow pine timbers were saplings long before Columbus; they were some of the oldest timbers on the Island,” said Allan Miller, father of Edible Vineyard editor Tina Miller, and the man who would become the builder of the Black Dog Tavern.

Miller had a long history of summering on the Island as a kid, and moved here in the ’60s after dropping out of prep school, and worked with Daniel Manter, an old-time Island carpenter. But Miller wanted to learn more, and eventually went on to work with David Douglas, Bob Douglas’ brother. “I got a full tutorship between working for David, who taught me about old houses, and Bob, who filled me in on boats,” Miller said.

One day while Douglas and Miller were having breakfast at the ArtCliff Diner, the two talked about how great it would be to have their own restaurant that served food you’d actually look forward to eating.

Douglas had the land — he owned a site on the shore of Vineyard Haven Harbor, occupied by a dilapidated boat shed called Captain Clem Cleveland’s Hickory Hall. And Douglas had the timbers he had acquired with the purchase of the cannon.

“Douglas’ vision was to build a new building that looked old, and that’s where I came in,” Miller said. “I had learned much of that from working with David Douglas.”

“I sketched out the design for the building on the back of a napkin,” Douglas said. “It wasn’t very complicated, it had to be this long, this wide, and this high because that’s how much lumber we had. And you didn’t have to worry much about permits in those days. I don’t think they even had a building inspector in Vineyard Haven.” Miller held tightly onto the sketch on the back of the napkin — it would serve as the blueprint for the new restaurant.

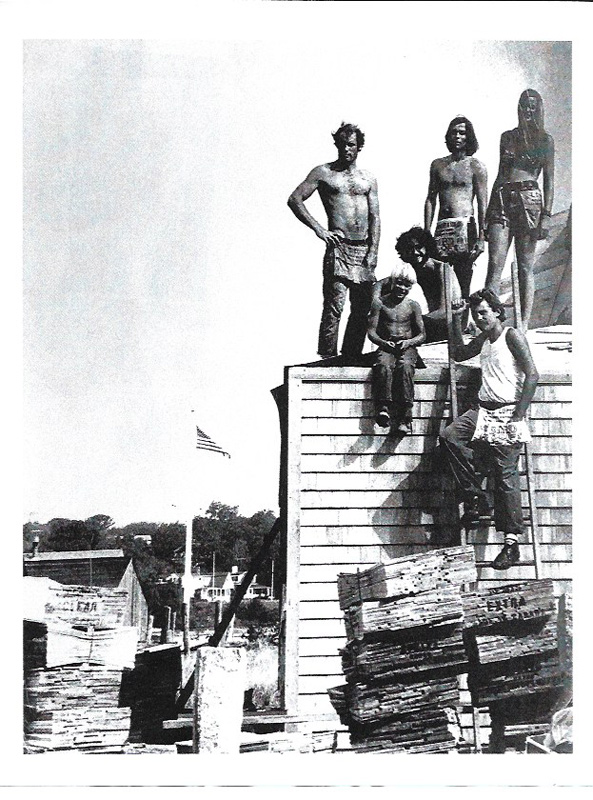

Miller and his crew started building on July 13, 1970. “You have to understand that it was a whole different time for building on the Vineyard 50 years ago,” Miller said. “We didn’t spend a lot of time getting permits and that kind of stuff in those days.”

Miller’s crew consisted of a nucleus of several people. “We had Roy Hayes, who was already a contractor, so he had the most skills,” Miller said. “There were Jack Mayhew, Lisa Fisher, and Tommy Reynolds, and Doug Higham, who was a boat builder, and he helped me out with the timbers.”

Nobody was getting rich on the job; back then carpenters were making about $3 an hour, but Miller considered himself lucky to have assembled such a fine group. “The crew we put together had a lot of enthusiasm,” he said, “they backed each other up, helped each other out — it was a high-energy period.”

Jack Mayhew had met Miller when Miller was building a barn not far from Jack’s parents’ house in West Tisbury and Mayhew went to check it out, and discovered, much to his fascination, that Miller was building a wooden car. “He took an old ’50s truck frame that had an old flathead V-8,” Mayhew said, “and stripped everything else away and built a wooden car on top of it.” Miller would later take the wooden car to California and back, accompanied by his partner Nancy Safford, who would go on to make major contributions to the running of the Black Dog. When he came back, Miller hired Mayhew as a carpenter. Mayhew had nothing but praise for Miller’s skills as a builder and his easygoing, pragmatic style.

“‘Don’t worry about it,’ Mayhew said Miller would say. “‘It’s just wood. If it’s not right, you can take it apart and do it again’ — that was his whole attitude.”

“Having all the beams was wonderful,” Mayhew said of the yellow pine beams, “but they were enormous, and moving them around proved to be a problem.” But the ever-resourceful Miller had a workaround that made moving the beams manageable. He went to the Vineyard Haven dump and found an old Buick lying upside down. He cut off the rear axle with the two wheels and tires on it, and brought it back. “We’d jack up one of the beams,” Mayhew said, “lash it onto the axle, and walk it over to the building site. When we had to get a beam over to the site, we’d say, ‘Time to get the Buick.’”

It took roughly six months to build the Black Dog, an enviable time even by today’s standards. It opened its doors on Jan. 11, 1971.

The Vineyard Gazette published an article in September 1970, describing the building as it neared completion: “The building, which includes a variety of architectural designs in tasteful combination, will probably be the most ruggedly built wooden structure on the Island today,” the article read. “Its lower story [will] contain a spacious dining room, with a huge fireplace.”

“The fireplace was nine feet, two inches,” Miller said. “David Douglas had a house in Essex with a nine-foot fireplace, and I suspect Capt. Bob made ours nine feet, two inches, just so it was bigger than his brother’s.”

“The interior is especially interesting,” the Gazette article went on, “for the main timbers are from old mill buildings. Dating from before the War of the Rebellion, they are 10- by 10-inch hard pine.”

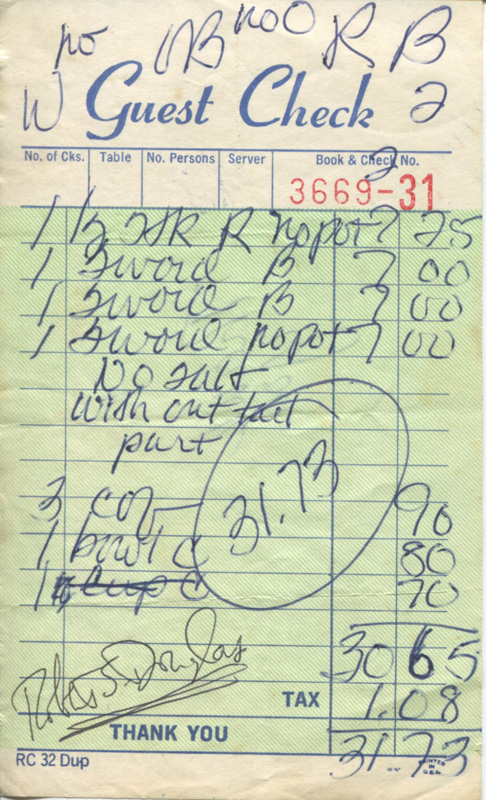

The article quotes Miller as saying, “The specialty of the place will be its chowder. The recipe will be that of Mrs. Sally Knight of Vineyard Haven, whose culinary skill is widely known.”

The reason that Miller, the builder of the Black Dog, is the one commenting on the cuisine is that he had an unusual arrangement with Bob Douglas. In addition to building the Black Dog, he agreed to run the restaurant for the first year. Choosing Miller to run the restaurant might not have seemed like the obvious choice. As a teenager he had worked at the Edgartown Kafe, starting as a dishwasher and working his way up in the kitchen. He had also worked briefly in a restaurant in Santa Barbara, but going from having summer jobs to opening up a new restaurant was a bit of a stretch.

“There were a lot of people who didn’t know what they were doing,” Miller said, “myself included — I was terrified. I’d just wake up in the morning and try to figure out the best I could do — everyone was in the same boat.”

Miller would have to draw on every resource he had, and that included relying on the kindness of strangers, “People would come out of the woodwork and do the nicest things,” Miller said. Soon after the restaurant opened, an elderly woman came up to Miller and gave him a little box with a handle that held a 12-piece silverware setting. “She was so sweet,” Miller said, “she said, ‘I just want to be part of the Black Dog, I want you to have this silverware caddy so you’ll have a place to put your silverware.’”

And of course there was the redoubtable Sally Knight, she of the fabulous chowder, who worked as a cashier at the Black Dog, and made chowder at home and lugged it down to the restaurant in a jug. And refused to take a penny for her efforts.

But perhaps one of Miller’s greatest strengths was that he wasn’t afraid to break some rules. For instance, there was no charge for a second cup of coffee — he encouraged staff to give customers as much coffee as they wanted, on the house.

In addition, everyone got a demi-loaf of homemade bread when they sat down to dinner. “That was a huge idea at the time — earthshattering!” Miller said. “The bread was baked using honey instead of butter, and it was delicious.”

Jack Mayhew, who went on to become the baker at the Black Dog, said that Black Dog bread and desserts became so popular with customers that Douglas bought the old fire truck garage on Water Street in Vineyard Haven and converted it to a bakery, which is still operational today.

In another break with tradition, Miller allowed the waitresses to wear whatever they were comfortable with on the job, in stark contrast to most restaurants which required waitresses to wear “uni’s.” “Remember, it was the ’70s, and the no-bra look was in,” Miller said, “and that wasn’t exactly bad for business.”

Deborah Mayhew, Jack’s sister, worked as a waitress in those early days, and described the scene as “loosey-goosey and crazy.” “We were a happy family of partying hippies,” she said, “and Allan set the tone.”

She recalled an incident when one of the waitresses dropped a tray of dishes in the middle of the dining room, and Miller berated her loudly. “We all had to laugh because he was just putting her on, he had that kind of rapport with the staff,” Mayhew said, “but the customers weren’t in on the joke, and they were pretty shocked — which made it even funnier.”

And then there was Frieda Florintine. One night over drinks, Miller mentioned to Island artist Stanley Murphy that he would love to have a great nude painting of a voluptuous woman, the kind that hung over the bars of fancy men’s saloons in the good old days. Murphy loved the idea and created the painting, dubbing the lady “Frieda Florintine.” There was, of course, one small detail. The Black Dog didn’t have a bar over which to hang the painting, but the painting found a place on the wall in the kitchen, which because it was open to the dining room was in full view of customers.

“Captain Bob wasn’t crazy about Frieda,” Miller said. “His taste in art tended to lean more toward nautical prints, but I loved it, and when I left to go to open a restaurant in Florida, I took her with me.”

As anyone who has worked in a restaurant can attest, it’s even more than a full-time job. Nonetheless, Miller and Mayhew and a few of their pals wanted to keep their hand in carpentry, and started a small company called the Lazy Brothers. Miller even wrote up what he called a Constitution for the Lazy Brothers. Because they still had their day jobs, they had to limit their hours to about 16 a week. ”Thus the Lazy Brothers,” Mayhew said.

Every month on a full moon they would have a business meeting at either the Lampost or the Ritz Bar in Oak Bluffs.

The Lazy Brothers would not work on anything built after 1880.

And they never did estimates, because “you never know what you’re going to find,” Mayhew said. “We’d just tell customers, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll do it if it takes every penny you’ve got.’”

Bob Douglas had originally asked that Allan Miller stay on as manager of the Black Dog for one year, but after five years, Miller decided it was time to call it quits. The restaurant was in good hands, and Miller headed to Key West, where he ran a restaurant called Pepe’s Cafe, which he sold in 2017. Today Miller is happily retired and living in Boothbay Harbor, Maine.

And the Black Dog?

It’s doing just fine, as well.