On a foggy evening on April 23, 1927, the fishing schooner Etta M. Burns was sailing back to New Bedford when the helmsman fell asleep and the boat washed up on the rocks off Squibnocket Beach in Chilmark. As the surf battered the ship, bottles of liquor were released from the ruptured hull and washed up on shore.

The news spread fast around the Island, and people swarmed to the beach, trying to salvage the bottles while Chester Poole, an ardent prohibitionist who lived about a mile up the beach, smashed every bottle he could find.

But in retrospect, Poole got the last laugh, because the bottles that washed ashore were marked Old Mac Scotch Whisky, but they had come not from Scotland but from a rusty steamer anchored 30 miles off Montauk. They were all totally rotgut.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the 18th Amendment, a constitutional ban on the production and sale of alcoholic beverages that can be seen as the very definition of unintended consequences. Rather than eliminating liquor, this act did more to instill a culture of drinking in a thirsty nation than 100,000 happy hours.

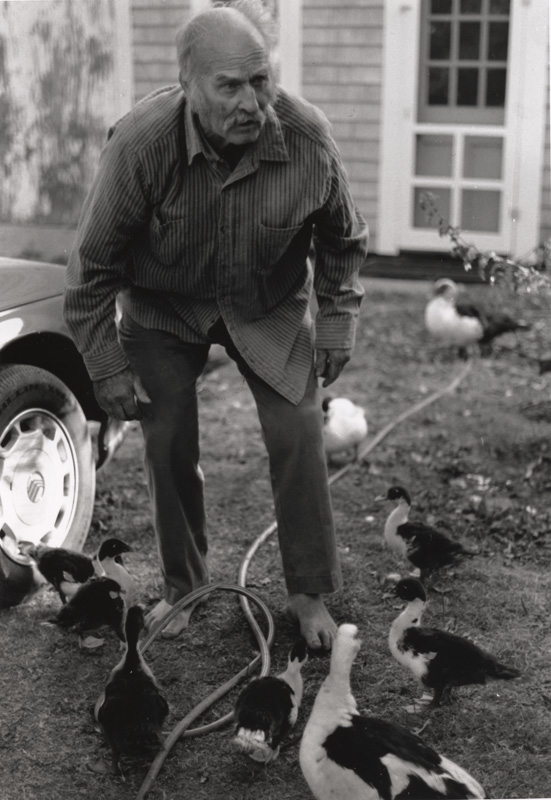

As Craig Kingsbury told Linsey Lee, the M.V. Museum’s oral history curator, “Hey, when Prohibition was going good, be a hard job to throw a rock and not hit on a booze establishment somewhere [on the Island].”

In fact, the Vineyard hosted enough bootlegging, rumrunning, moonshining, and other Prohibition-era activities to merit its own film, “Bootleggers on Martha’s Vineyard — Craig Kingsbury Talks about Prohibition,” produced by Lee and Kate Feiffer. You can see it here: bit.ly/MVbootleg.

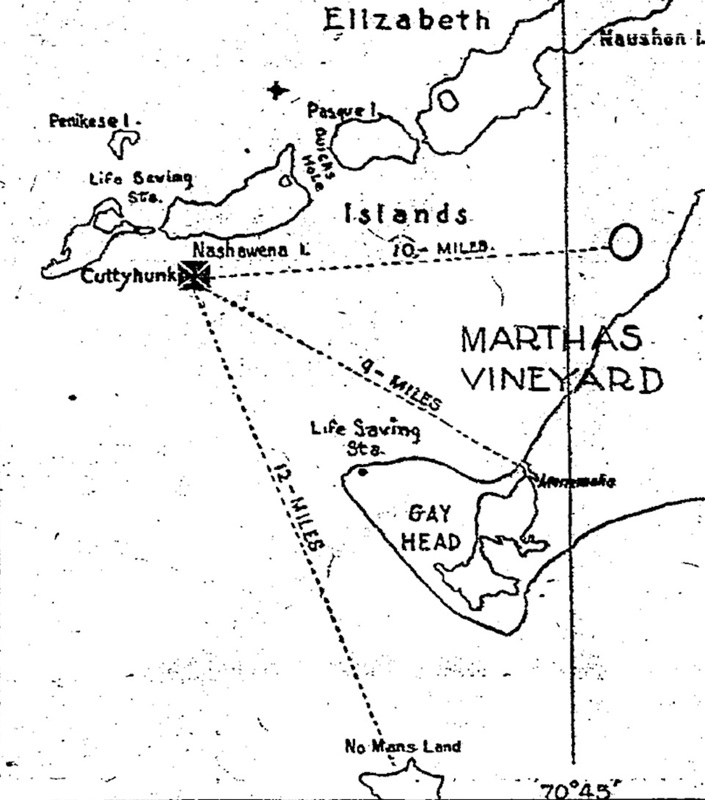

But Vineyarders were not only doing their fair share of consuming liquor, we were doing our fair share of supplying it, as well. In 1920, boats carrying liquor were prohibited from coming within three miles of the mainland. In 1923, the limit would be extended to 12 miles, which once again resulted in unintended consequences. The Coast Guard had a hard enough time patrolling the waters within three miles; patrolling within 12 miles made it even tougher.

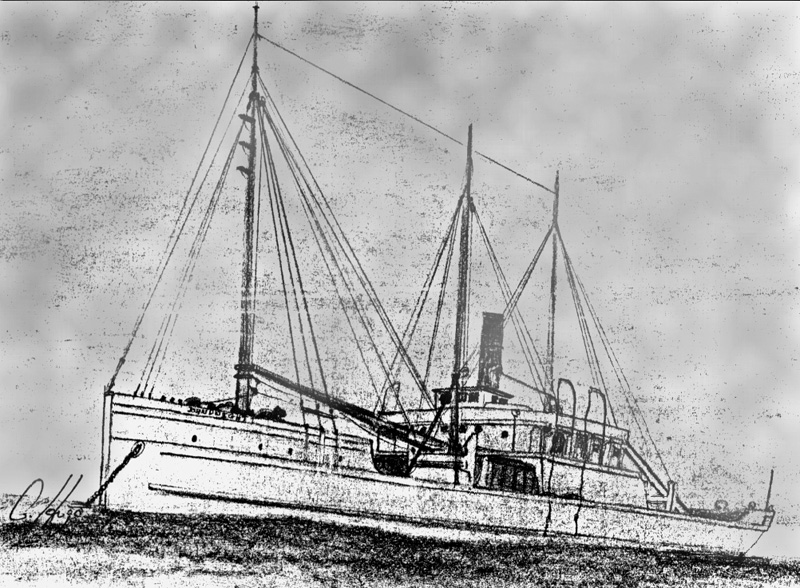

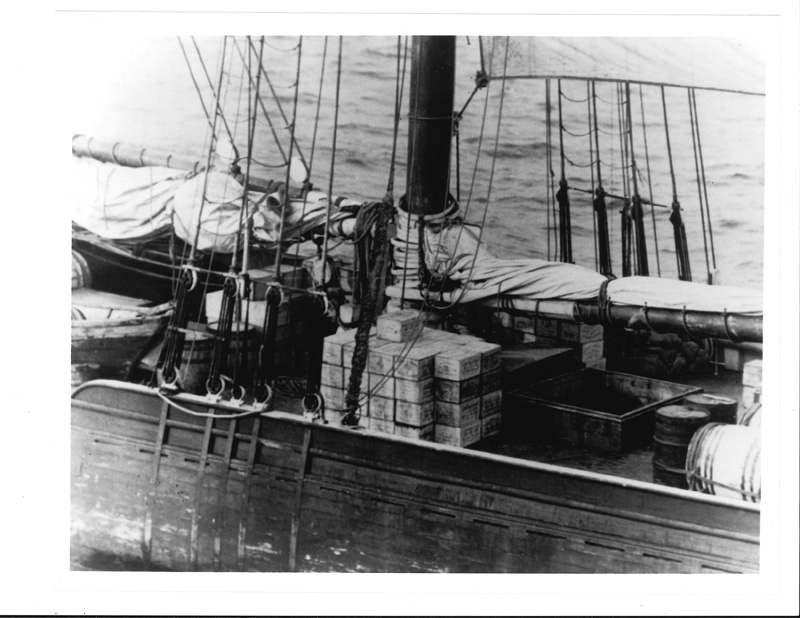

Just beyond the 12-mile limit, ships laden with liquor, often flying British and Canadian flags, would lay in wait, safe from the Coast Guard, and smaller boats would shuttle back and forth to these “mother ships” to buy liquor and smuggle it back to the mainland. The long line of these supply ships extended down the East Coast, and was known as Rum Row.

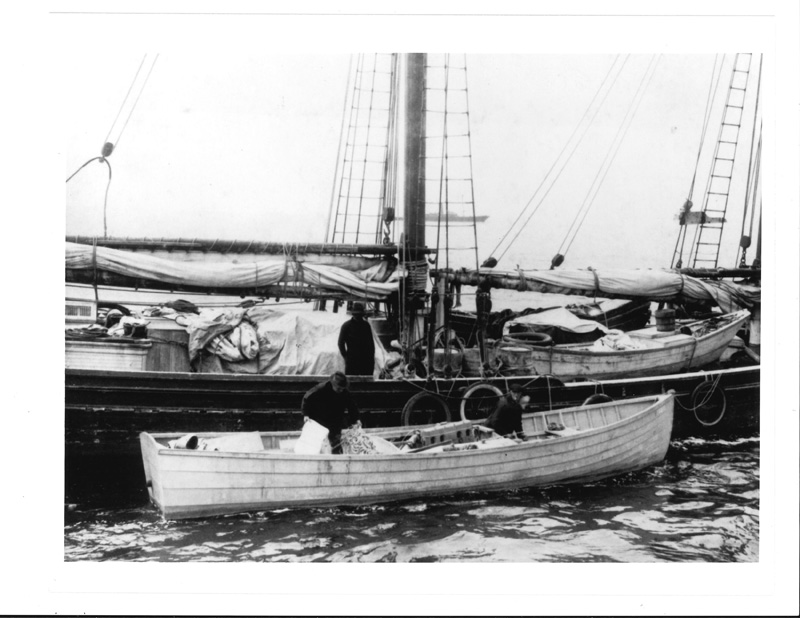

The August 1996 edition of the Dukes County Intelligencer does a good job of discussing the Vineyard’s role in rumrunning. “Some of the most successful rumrunners were commercial fishermen,” it said and there was no shortage of fishing boats on the Vineyard. Since these boats were fishing out by the mother ships, they appeared innocent enough to the Coast Guard, and it was easy for them to pick up a load of liquor to supplement their catch.

“By the time they returned to port to sell their catches,” the Intelligencer said, “they were carrying two separate cargoes: one visible was the layers of fresh fish bedded down in chopped ice, the other at the bottom of the hold hidden from view was the real cash crop, liquor. The disguise served them well, and it is little wonder that big city bootleggers sought them out for delivery. The money was good and the risk was low, at least so the fishermen were told.”

But in addition to the fishing boats, many Vineyarders who had a fast boat and a heightened sense of adventure would wait for a moonless night and venture out to the supply ships themselves.

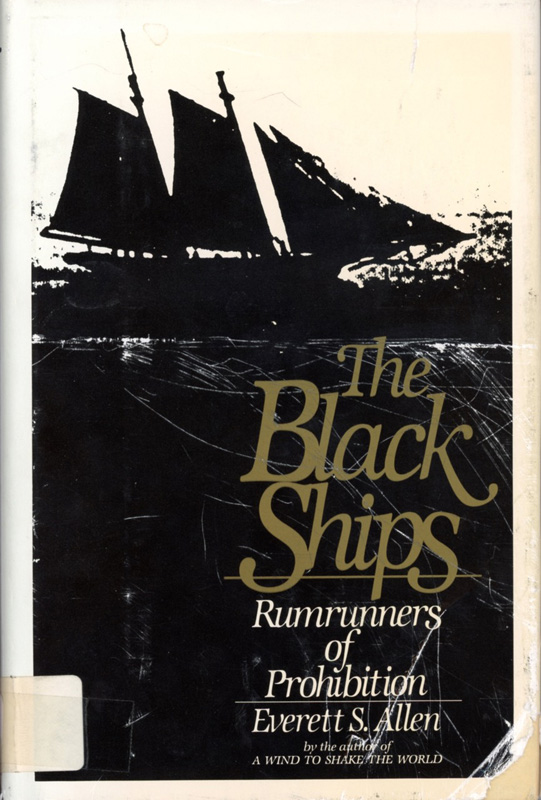

Perhaps the most famous rumrunner of them all spent a fair amount of time operating out of the Vineyard. Bill McCoy would stock up his schooner in the Bahamas, and earned the nickname “the Real McCoy” because he never watered down or adulterated his product, at a time when less scrupulous smugglers were mixing their product with turpentine, wood alcohol, or prune juice. The book “Black Ships: Rumrunners of Prohibition” by Everett S. Allen explains the reason for McCoy choosing Gay Head (now Aquinnah) as his Vineyard base of operations: “McCoy recalled that many of the Gay Head residents were Indian:

Indians are ideal people for a rumrunner to live among. They don’t ask questions. They don’t talk to strangers. They haven’t any particular use for law or the government. I stayed with them for several weeks.”

The book also provides a glimpse into life on a rumrunner far from home: “My crew were all American citizens who hoped to sometime return to their native land,” McCoy said. “To avoid recognition when their reprehensible past was behind them, they all grew beards of untamed luxuriance, and since the schooner had been out for a long time and fresh water was scarce, they rarely washed. They looked like Airedales and smelled like camels.”

Through the lens of time, rumrunning can take on a sanitized patina, appearing to be a harmless cat and mouse game between the Coast Guard and daredevil mariners. But make no mistake, it often led to dire consequences. The Intelligencer says, “It was a nautical version of the American Wild West. Piracies and hijackings were so common that most captains and crews armed themselves.” Take the case of the rumrunning vessel John Dwight.

According to “Black Ships,” in 1923, seven corpses were found floating in Vineyard Sound, along with many barrels of bottled Canadian ale. They were believed to be from the John Dwight, which had capsized off Cuttyhunk the day before. An eighth body was found face-down with his skull, crushed in a small boat drifting off Menemsha Harbor.

Allen writes in “Black Ships” that “it was like a return to the long-gone days when pirates roamed the Seven Seas.” What exactly happened may never be known. According to the Intelligencer, the John Dwight had an encounter with the steam yacht Flit, and a grisly fight ensued. Beyond that, not much is known.

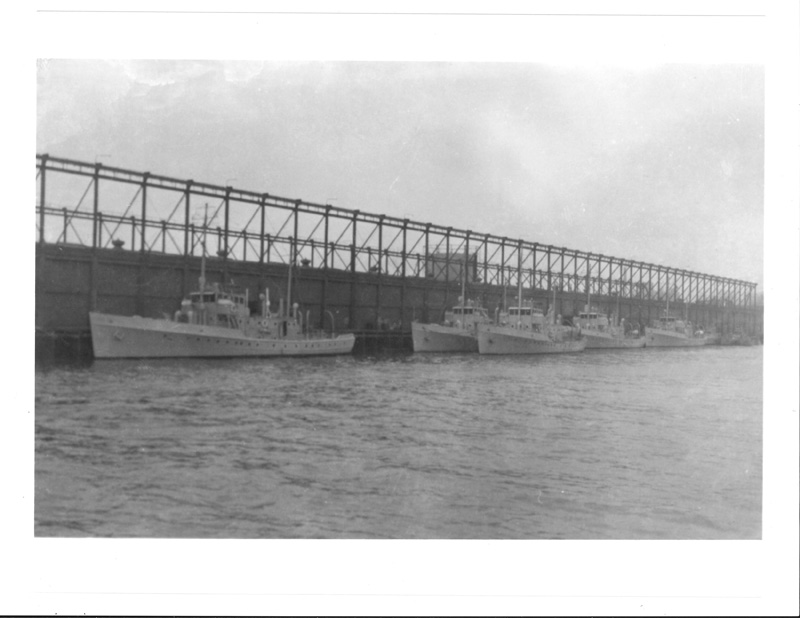

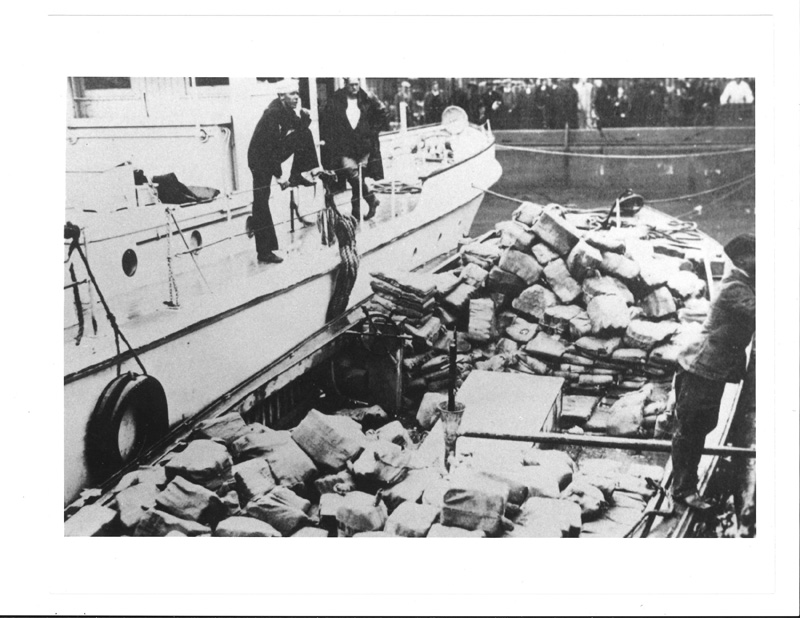

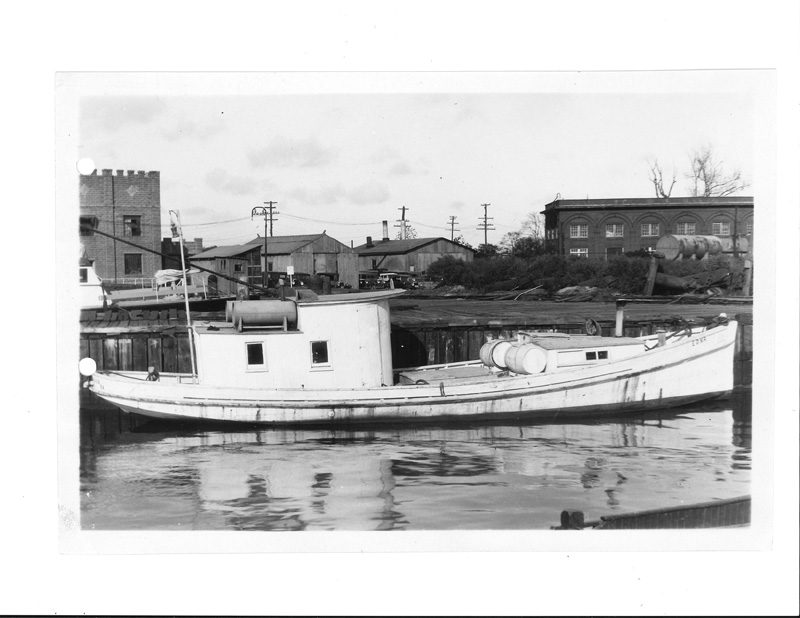

As rumrunning became more common, the Coast Guard stepped up their game, becoming more and more vigilant and suspicious of returning fishing boats. Not to be outdone, the smugglers had some tricks up their sleeves as well. According to “Black Ships,” the rumrunners countered by building specialized vessels, high-power speedboats 40 to 50 feet long, powered by converted World War I airplane engines that were capable of speeds of 35 knots, even when fully loaded.

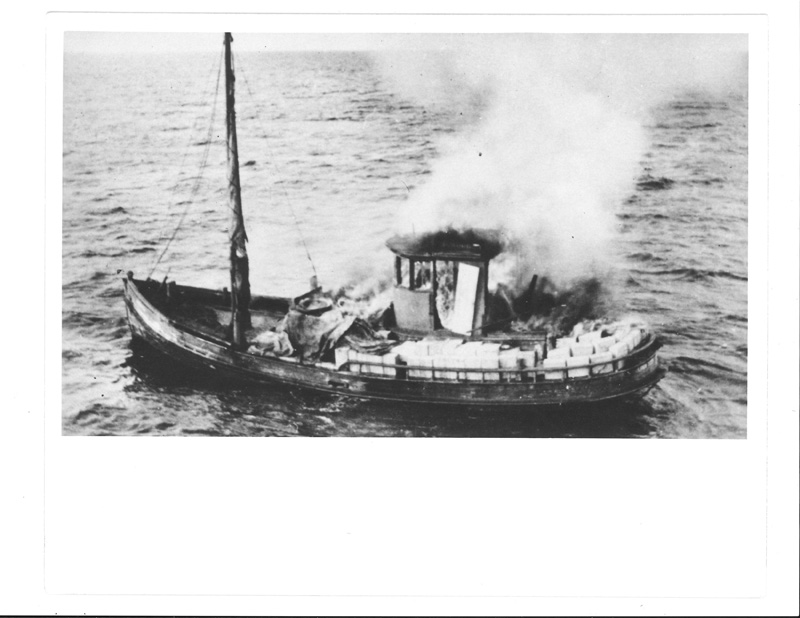

One of the Coast Guard’s most worthy adversaries was the Vineyard’s own Frank Butler. He was one of the most successful rumrunning skippers, and he operated both fishing boats and speedboats. One of his many innovations was dropping dirty black engine oil on the exhaust manifolds, thereby creating a dense cloud of smoke to obscure his getaway. He also developed the double-bottom boat, to conceal his cargo from the Coast Guard. But his invention of the Nola, an armor-plated speedboat, proved to be Butler’s undoing.

In December 1931, Butler and the Nola were steaming down Vineyard Sound with the Coast Guard — machine guns blazing — in hot pursuit. But just as Nola appeared to be getting away, machine gun rounds hit cans of alcohol on the deck, and the Nola went up in flames, and sank to the bottom of the sound.

This was 1931; Prohibition would be overturned in 1933. Rumrunning had made Frank Butler, Bill McCoy, and countless others very wealthy men — to others it had been far less kind.

According to Bow Van Riper, research librarian at the M.V. Museum, Martha’s Vineyard was pretty evenly split between the “wets,” people in favor of alcohol, and the “dries,” people opposed to it. For the purpose of this article, I chose to concentrate on the rumrunners who supplied the liquor — they had more vivid stories to tell. To tell the stories of people sitting around abstaining from alcohol would be — pretty dry.

From Vineyarders who were there

Linsey Lee, oral history curator for the M.V. Museum, compiled quotes from Vineyarders who had firsthand recollections of Prohibition for a 2016 exhibit at the Museum called “Prohibition.”

“The Coast Guard boats were out in the shoals, and most of the time Frank Butler would slip by them. And then, of course, when they were shooting, if that boat was out here and they had to shoot toward land, they couldn’t shoot. So Butler knew the water good enough, he just skimmed the rocks here. I never heard of him going up on the rocks.”

–Charles Vanderhoop, Aquinnah (1921 – 2001)

“Well, the quality [of locally distilled liquor], to us local hillbillies, was strength. And you tested that. You went in, everybody had a coal stove. You take the lid off, spit a mouthful of that in the stove and see how high the blue flame came. And that would show you the strength of the moonshine.”

–Craig Kingsbury, Vineyard Haven (1918 – 2004)

“I knew there was one [bootleg still] down at the corner of County Road and Barnes Road. The fellow that manufactured stuff, his nickname was ‘Half Pint.’”

–Elisha Smith, Vineyard Haven (1923 – 2013)

“And if they were being chased, or if they thought they were going to be chased, they’d dump it [the liquor], and come back and get it.”

–Gale Huntington, Vineyard Haven (1902 – 1993)

“And then they also used to shoot across the bow. You’d hear them out in the sound. We’d sort of see them, but what you’d hear is the shooting. And so then you’d rush out to look.”

–Margot Wilkie, Chilmark (1912 – 2013)

“Rumor had it that some of the influential people of the Island frequently used the steps of the Chilmark Church parsonage to hide their bootleg liquor under.”

–Willis Gifford, West Tisbury (1890 – 1987)