If you are at Inkwell Beach this summer, and you see a man who appears to be stealing small cups of water from the ocean, it might be Jesse Ausubel. He likes to swim there every day, and his water samples offer a glimpse of the sea that beats the finest swim goggles.

Ausubel samples environmental DNA, looking for scraps of biological material that can reveal, by genetic analysis, exactly who swims, drifts, or scuttles nearby. He’s detected striped bass in Upper Lagoon Pond, river otter in Mill Pond, and of course, lots and lots of homo sapiens.

It’s more than just environmental DNA (eDNA) broadening our view beneath the sea. Recently, National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration scientists, equipped with spectrometers, proved they can determine the species, age, region and even diet of a fish using only its ear stone, or otolith. They can also do this to the stones in the belly of a bigger fish — now each tuna is a traveling library of the ocean around it. To a layman, all this new insight raises a perennial question: How are the fisheries, and where are they headed?

Ausubel, as it turns out, is a great person to ask. In addition to his recent work with eDNA, he is Director of the Program for the Human Environment at Rockefeller University, and works at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Most inspiringly, for those curious about the Island’s fate “at the tail end of a 1,000-year fishing spree,” as one author put it, Ausubel helped carry out the international, decade-long Census of Marine Life.

“The honest answer,” Ausubel told me, “is nobody knows.” There are estimates and projections, especially for commercially important fish, but “nobody has really done a full, detailed scenario out to say, 2050, for this region, looking at it in this kind of detail. There’s no single answer to the question of ‘what’s it going to be like?’”

Of the world’s 66 Large Marine Ecosystems, the Vineyard lies in number 7, the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf, bounded on each end by Nova Scotia and Cape Hatteras. The Island belongs to the Georges Bank unit, between the Gulf of Maine and the Mid-Atlantic Bight.

Georges Bank, a submerged part of the North American mainland 60-odd miles east of the Cape and Islands, is a fishery so valuable that the dibs called on it went all the way to the Hague. They settled things by shaving off a northeast slice for Nova Scotia.

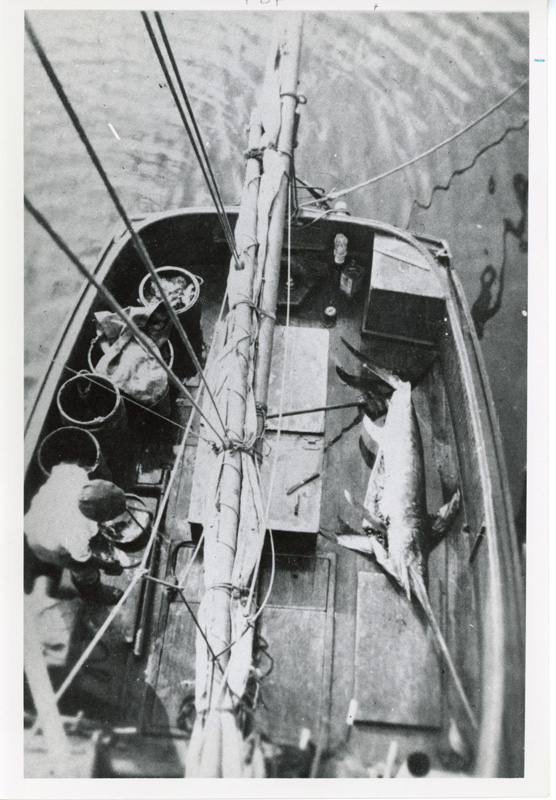

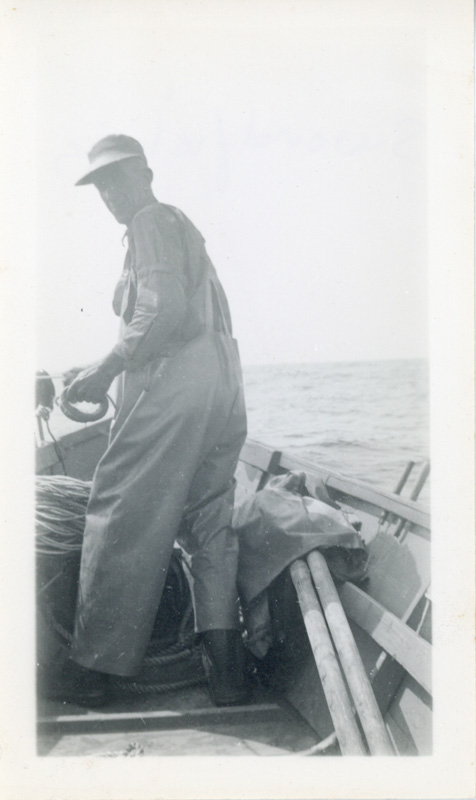

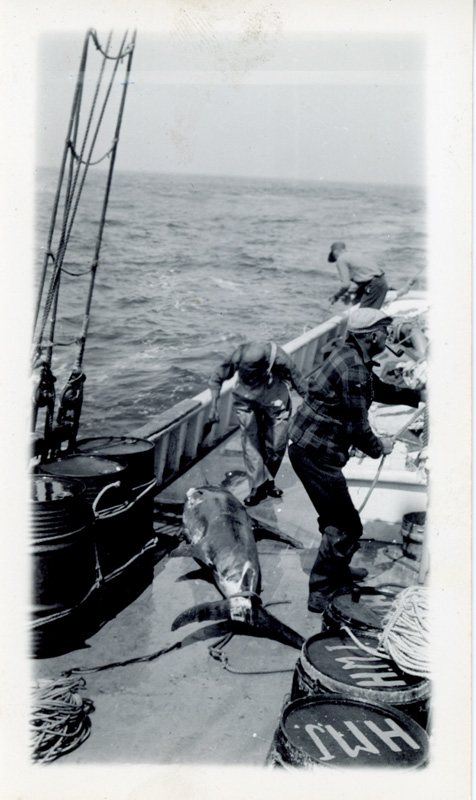

Island fishing boats have been speared by swordfish on Georges Bank, blown up by U-boats, swamped by ocean liners, lost in storms, and on and on, all in pursuit of the catch. Once, in the years after World War I, a labor strike on the Eastern seaboard led to a Georges Bank expedition crewed entirely by captains — their picket-crossing haul of swordfish to New Bedford was a record 20,000 pounds.

Those days are long gone. Harpooned at first from small catboats out of Edgartown and from schooners on Georges Bank, by the 1970s Island boats were spotting swordfish with airplanes and racking up huge catches.

By the late seventies Island boats had ventured all the way to the Gulf of Mexico in search of swordfish, and even those stocks were collapsing. In the 1990s, Louis Larsen, a legendary Island fisherman, recalled to historian Clyde MacKenzie Jr. that he “gave up swordfishing right after our plane went from the peak of Brown’s Bank [in Nova Scotia] to the southeast part of Georges and didn’t see a single swordfish.”

Overfishing, infamous, convoluted and acrimonious, has been the main culprit in fisheries decline, on Georges Bank and in waters nearer to shore — so it is no surprise that it still presents the top threat to our region, according to results from the Census of Marine Life. Lagging just behind are habitat loss, pollution, temperature change, invasive species, hypoxia, and acidification, in that order. Intensifying greenhouse gas emissions will cause or exacerbate several of these.

Marine heatwaves have been an increasing fact of life on the Bank — last year saw three separate heatwaves in the summer and fall, with the strongest, last August, pushing the average water temperature more than three degrees celsius higher than average.

A recent paper, by NOAA’s Dr. Jon Hare and other researchers, is a speculative tally of winners and losers in a warming ocean. Some species, including black sea bass and bluefish, might actually improve their productivity over the next several decades (happy news for Island anglers, and those who feast on their take).

The species in the green, however, are dwarfed by those in the red — which include many Island staples. Atlantic cod and salmon, already devastated, are high in the red, as are halibut, haddock, several species of skate and flounder, alewives, oysters, and both sea scallops and bay scallops.

This vulnerability can mean many things. “One would need to try to look at all of the seven or more threat factors at once, and how those are changing in the region,” said Ausubel, “and then you have to look at them not only in relation to the fishes, but also to the squid and the octopus, and the shellfish, the molluscs, like the clams and the scallops, or the decapods like the crabs or the lobsters.”

On the topic of invasive species, for example, “people could spend a whole career just worrying about the effects of the Japanese green crab in the coastal ponds on Cape Cod and the Islands,” he said.

One thing that will certainly affect how the most at-risk species will fare is how they have been faring. Daunting as the big picture is, I asked Ausubel to give me a brief rundown of some Island classics. After a little thought, he began to spool out line.

Cod, the namesake of our region and the engine of a powerful extractive economy for hundreds of years, is “now about 3% of what it was in 1800,” he said. “So, it’s not extinct by any means. In March, I’ll get cod DNA, so they’re swimming around, but there aren’t enough of them to support a commercial fishery, and not enough to feed many people.”

He waxed gastronomic: “I personally like cod very much. It’s a kind of vanilla fish, which you can put red sauces on or white sauces on, or you can deep fry it,” he said. “Flounder, of course, flounder, fluke, sole, used to abound and they are now tightly regulated — those are also very simple tasting, lovely, delicate fish, all you need to do is saute it in butter or put some lemon on it and a little garlic and oil.”

He continued, “There were lots of salmon, as far south as the Connecticut River, although not really farther than that. Salmon was also a case where it was so common it was not particularly esteemed.” Dammed rivers dealt a huge blow in the 1800s, and recent recovery efforts, like the one on the Merrimack River, have so far ended in failure.

Ironically, Atlantic salmon are now very popular to eat, and several million pounds of them have already gone to market in Massachusetts this year — arriving from fish farms in Norway, Iceland, Chile, and the Faroe Islands.

A few items are still plentiful enough to export from the Island, namely shellfish from the Vineyard’s own aquaculture industry. “There was always the shellfish,” Ausubel said. “The very abundant oysters and clams. Those are a success story. We still have a lot of quahogs, and the oyster farming is really quite successful.”

“Steamers, it’s a bit more problematic,” he hedged, “but they’re surviving, just not flourishing the way the quahogs and the oysters are. The scallop fishery has become bigger — scallops are very fashionable and good to serve in restaurants.”

The sea scallop fishery on Georges Bank seems to be some of the only revenue left for local fishermen. “It used to be that the small bay scallops were considered more choice,” said Ausubel. Changing tastes in that regard were demonstrated in Menemsha this April, when 500 pounds of sea scallops sold straight off a boat in two hours.

These deepwater molluscs are one of the few species to have actually flourished during the multi-decade closure of Georges Bank. Sea clams are doing well too, according to NOAA, and go into most chowders around New England.

Lobster eaten on the Vineyard is sometimes local, but as the Island population swells in the summer — accompanied by the anticipatory loosening of belts and the melting of butter — restaurants and fish markets call in reinforcements from Maine and Canada.

Next: “Now conch, of course, that’s a taste,” said Ausubel. He noted that although used by many cultures, conch, more properly called whelk, never quite reached the mainstream palate in the U.S.

Vineyard Sound is one of the main whelk fisheries in the state, but get this: Until 2010, scientists didn’t even know the age of maturity for a whelk. In other words, the state’s minimum harvest size had been arbitrary for decades.

Although size regulations are catching up with that slow-growing snail, it’s not hard to find other scenarios where science lags behind exploitation. A lack of data now will muddy the story we tell later — our fish story runs the risk, as with all fish stories, of becoming just another anecdote.

“Everybody is expecting things to change, and unless we start doing regular collections, we’re not going to know,” said Ausubel. That is why he is pushing to start a baseline series of eDNA collections around the Island, like what Audubon has been doing for years with the Christmas Bird Count.

Ausubel pointed to striped bass, which exemplify the wild ride that Island species have already been on. “They were plentiful and then became very scarce, and have come back somewhat, thanks in large part to regulation,” he said. The first striped bass regulation in Massachusetts dates back more than two hundred years, but the fishery is still troubled enough that it won’t be fished in its namesake tournament this year.

As Islanders of all stripes try to focus on a hazy future for the creatures in their seas and on their plates, it might be useful to look back, to histories of harvest and husbandry, and note how quickly things can change. Testaments to fishes past are chockablock in old editions of The Duke’s County Intelligencer (newly digitized by the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, and truly a balm for those suffering from free time and a deficiency of historical context).

Yale historian Paul Freedman, writing about the history of American cuisine, wrote that “the former abundance of American fish and game is striking,” and that the sheer amount of diversity that once graced American menus “demonstrates the essential poverty of the twenty-first century’s natural, as well as its culinary, environment.”

An aspiration to increase the diversity and abundance of marine life around the Island could strengthen the resilience of the Vineyard to future changes, and, as demonstrated by the world’s best managed fisheries, bring livelihoods to fishermen and local foodways to Island eaters.

This doesn’t mean we should go back to eating green turtle steaks with green peas, like New Englanders did in the 18th century — as Freedman writes, “given the evolution of taste over a century and a half, many of our forebears’ food choices will strike us as less than congenial.”

As with all ecosystems, there is no neat line between shore and ocean, biologically, culturally, or commercially. When herring flowed by the tens of thousands up Mattakesett Creek, in Edgartown, they were harvested as bait for cod on Georges Bank and farther afield. Scraping the bottom of the food chain to feed the top — this is still common practice in the seafood industry, especially on fish farms, where baitfish are turned into protein for bigger fish.

Ausubel predicts a split, already begun, between these farmed fish and wild fish. “In this region, we may be importing striped bass that are grown in tanks in Western Massachusetts,” he said — and that may be the only option if Americans want to eat more of it than the ocean can consistently provide.

Recent ventures — a boom in Island grown oysters, or the promising return of Squibnocket herring fostered by the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head — point toward a Vineyard seafood landscape that is more husbandry than forage, a dynamic stock to be studied and stewarded, rather than a silvery hoard there for the taking. The challenge is convincing all the neighbors to cooperate on one large, backyard garden.