We Islanders are generally a cooperative sort, generous with our time and resources, always willing to help one another out. But as with any limited resource, we can get a little funny around here about space — the space we think we alone have rights to: our private beach, that pond my family used to own, this parking spot I’ve been circling the lot for 15 minutes waiting for …

Thanks to forward-thinking landowners, government agencies, and a myriad of Island nonprofits, nearly one-third of that precious Martha’s Vineyard land is under some kind of development restriction. And because of our (usually) cooperative spirit, much of this land is open to the public. So no matter who you are or where you come from, you are welcome to experience the wonders of conservation land: hiking through shady forests laden with wild blueberries, kayaking in brackish ponds teeming with spawning marine life, or even watching Tisbury farmer Jefferson Monroe tending a flock of sheep in a wide-open field.

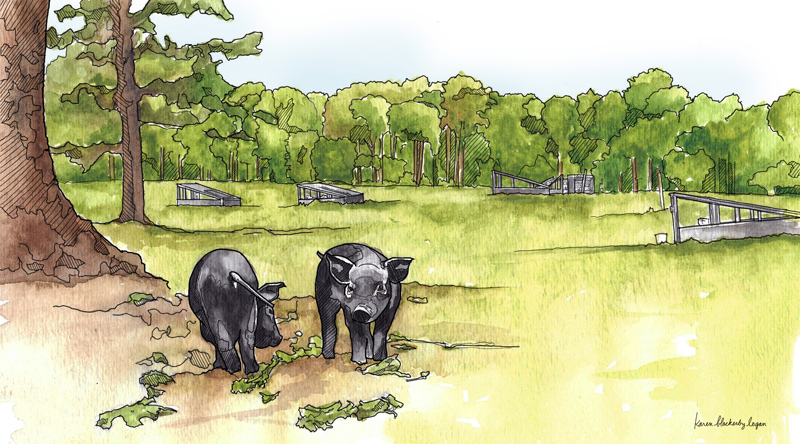

Jefferson has been farming on the Vineyard since he moved here to help run the Youth Hostel in 2005. Having spent years gaining farming experience working with Island Grown Initiative and Flat Point Farm, he was ready to start his own farm, but didn’t have the means to purchase the amount of land necessary to start his own. So when, in 2010, he learned that the M.V. Land Bank’s Tisbury Meadow property was available for lease, he jumped at the chance. The price was definitely within his range, as the Land Bank agriculture leases are set at an affordable annual fee of $10 per acre. He admits the property itself isn’t ideal for farming. It’s hilly and covered in poison ivy. There’s no water available, and farmers aren’t allowed to build housing on Land Bank properties, “but it’s land on M.V., so it’s better than nothing!” This upbeat attitude makes him the perfect farmer of public land. He admits it’s more work to take care of animals in a remote location, when water, fencing, and feed all have to be brought in. Fences have to be extra-secure, since the farmer can’t live onsite and won’t notice that someone has escaped until he is alerted by the authorities. Habitats need to be not only functional and durable, but pleasing to the eye, as the public will be able to scrutinize your work as they stroll around the premises with their birdwatching binoculars.

Amazingly, Jefferson doesn’t report having trouble with visitors to the property, or even dogs harassing his livestock. He chooses to focus on the positives — Islanders and visitors are used to being around farms, they appreciate the importance of local agriculture, and the bucolic charm of grazing animals. And lots of visitors mean help keeping an eye on things; someone will call you pretty quickly if something looks amiss.

The GOOD in his GOOD Farm is an acronym for Garden of Our Descent, referring to the decreasing availability of fossil fuels and need to move away from traditional, energy-intensive agriculture toward practices that are more resilient and localized. His mission is to increase positive impact on the land as much as possible. Along with conservation agencies like Vineyard Conservation Society, Sheriff’s Meadow, and The Trustees of Reservations, the Land Bank shares this positive-impact mission, and recognizes the benefits of agriculture on the land. Not only do they lease land for agricultural use, but they even have a herd of goats that moves around to “goatscape” different properties. Some of these agencies are also involved in managing agricultural preservation restrictions, or APRs, on privately owned farms, land being so valuable on Martha’s Vineyard that sometimes families can’t even afford to inherit it, let alone keep up a centuries-old farming tradition. These APRs pay landowners a portion of the land value to enter into an agreement that the land will not be developed in a way that is detrimental to the environment. In 2012, Jefferson was invited to put down roots at the Kingsbury Farm in Tisbury, as part of a Land Bank–managed APR. There he has been able to expand his sustainability practices and “self-renewing fertility,” like planting perennial vegetables and using animal waste to add nutrients to the soil.

In recent times of prolonged isolation, open spaces have become even more important, as a place to exercise our bodies and rest our computer screen–strained eyeballs. But even more important, I am inspired by the wholehearted hopefulness of partnerships like this. It is the epitome of Martha’s Vineyard — creative individuals working together to find solutions that benefit not only our community, but our planet.

We live in a very special place. One where, when we are feeling cooped up, anxious and cut off, we can take a walk among the blooming wildflowers, buzzing cicadas, and lazily munching goats, and remember that we’re all in this together.

Kate Tvelia Athearn is a writer, educator, and farmer based in West Tisbury, where she lives with her family.