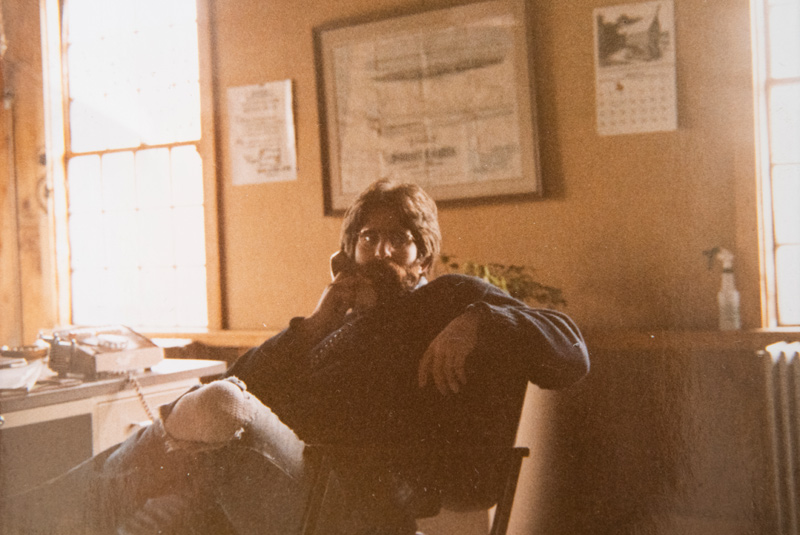

Bob Mone, owner of Mone Insurance, has a well-appointed office overlooking Vineyard Haven harbor. It’s decorated with a nautical motif; there’s a 5-foot admiralty model of a captain’s gig against one wall, a photograph of a fishing vessel in heavy seas across from his desk, another photo of three fishing boats lined up at the dock in New Bedford, and a photograph that brings back particularly fond memories to Mone of a fishing boat tied up to the dock alongside the offices of the Vineyard Co-op, a fish brokerage that Mone owned in a former life. And to hear him talk, it was quite a life.

“It’s everything that the insurance business isn’t,” Mone says. “Insurance is orderly and regulated; in the fish broker business there was a lot of flying by the seat of your pants. It wasn’t just an ordinary job, it was wild.”

The origins of Vineyard Co-op go back to a guy named Steve Boggess, who around 1970 ran Boggess Seafood out of Woods Hole on the pier over where the ferry shuttles back and forth to Naushon. Trip Barnes, who did trucking for Boggess, described him as “a college guy, kind of a yuppie. But he had a mind like a steel trap.”

But the Steamship Authority, which owned the dock where Boggess’s office was located, put the squeeze on Boggess and forced him to leave. So Ralph Packer agreed to build a dock next to his gas tanks on Vineyard Haven harbor and Boggess moved his business to the Vineyard.

Around 1975 Mone answered an ad looking for a manager at Boggess Seafood. At the time he was driving a milk truck on the Island and the only thing he knew about fish was that you buy them at a fish market. But he was a quick study and rapidly worked his way up through the ranks.

“I started out on the dock shoveling ice,” Mone said, “and then I moved to nailing lids on boxes. The money was good and it was a year-round job.”

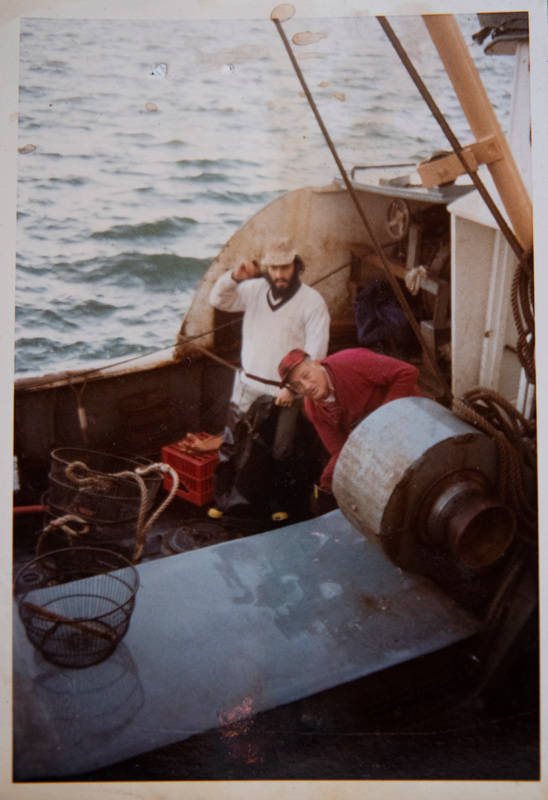

The next step for Mone was working on the big stainless steel chute unloading the boats where he would learn to sort fish by species and size. “There were about eight of us working on the chute,” Mone said, “and we could unload about 15,000 pounds an hour. It was quite a scene.” Eventually Mone worked his way off the docks and up into the office where he started selling. These were glory days for Boggess Seafoods.

The advantage that Boggess had over fish brokers in New Bedford was that the Vineyard was 20 miles closer to the fishing grounds. “Pretty soon we had all the best boats coming to us,” Mone said. “The big draggers from New Bedford and the smaller fleet of boats on the Island run by guys like Greg and Jonathan Mayhew, Jimmy Morgan, Harold Laury, and Buzzy Snowden; we did business with about 20 or 30 local boats as well.” But it wasn’t all smooth sailing for Boggess Seafood. “The folks in New Bedford didn’t like Boggess closing in on their turf,” Mone said, “so they sent some people over to try and shut us down.”

Trip Barnes, owner of Barnes Moving and Storage, did deliveries for Boggess at the time and said that the fish packers in New Bedford couldn’t get Boggess to stop, so they came after the trucks. “We were having a problem with Local 59 New Bedford Teamsters because we weren’t union,” Barnes said. “They even put a picket line in front of my house — the wife loved that.”

Ultimately an election was held at the Mansion House to see if the local drivers would join the union — at that point Barnes’ and Carroll’s drivers were working with Boggess and the motion was voted down. But the New Bedford crowd didn’t accept defeat gracefully.

“They couldn’t stop us legally so they tried to stop us by being tough,” Barnes said. “They’d wait for us and shoot at our trucks as we’d go up Route195 through New Bedford. One of my old trailers is up at John Keene’s (excavation company) and it still has bullet holes in it.” I spoke with Mike Barnes, Trip’s son, who was just a boy at the time and he said, “Yeah I remember that, I think I was in the truck at the time.”

“I’d get down to Fulton at night,” Barnes said, “and I’d head over to the Savoy Lounge or the Paris Cafe and a guy would sit down next to me and say, ‘Hey Trippy, going to be about half-an-hour, have yourself a drink.” Barnes, who has been on the wagon since 1989 recalls that there was some heavy drinking going on in those days. In the sleeper behind the seat in his truck there was a hole where he could drop the empties and they went into a box by the tool box where there were mothballs to hide the smell. “It would take me about a six pack to get to New York,” Barnes said.

When Barnes was on the road, in the days before cell phones, people would call his home to get in touch with him and often his daughter Elizabeth, who was 12, would answer and relay the messages to Barnes. “If she had to take a message,” Barnes said, “she’d say wait a minute until I get a crayon.”

Rather than deadhead back to the Vineyard with no cargo, Barnes would pick up furniture deliveries from New York. He’d just throw down a lot of sawdust in the back of the truck to mask the smell of the fish.

In 1980 Boggess expanded his business model to include selling fish filets. He called the new business Golden Eye and opened up an office in New Bedford which he managed, leaving the operation of the Vineyard office to Mone. Golden Eye unfortunately went bankrupt in 1985 and Boggess sold off his assets. But this actually opened up a door for Mone. While the bank was negotiating Boggess’s bankruptcy, another fish dealer from New Bedford approached Mone and asked him if he wanted to keep running the business. “The guy shows up in a Jag,” Mone said. “He said we’d go 50/50 and he’d put up all the money and I’d run the show. Then he handed me 50 grand in a paper bag.”

In time, Mone would take over full ownership of the company which was now called the Vineyard Co-op. He also did much to expand the sales of the company.

“Fluke come up north in the summer and go down south in the winter,” Mone said, so he came up with the idea of selling fish down south in the summer. “They love fluke down there,” Mone said. “There were all these places called ‘fish camps’ where they sold fluke, hushpuppies, and beer.” Hushpuppies are basically fried dough served as a side dish.

“I’d go down to Virginia and North Carolina and spend a couple of weeks talking to people and getting customers and before long, between 70 and 80 percent of our business was coming from down south.”

Times were good.

And then just like that, they weren’t.

At one point Vineyard Haven was the third largest fishing port in Massachusetts, behind New Bedford and Gloucester. But by the nineties, because of overfishing and regulations, the fishing industry collapsed. At its peak, the Vineyard Co-op was selling about 7 million pounds of fish a year. But by 1994 they were only selling about 600,000 pounds a year and there just wasn’t enough volume to make it worth it. Mone would sell the business to Warren Doty from Chilmark who operated a scaled down version of the business called Menemsha Basin Seafoods for a few years.

But don’t feel sorry for Bob Mone. Today he operates a very successful insurance business right down the road from where the old Vineyard Co-op offices were. “Toward the end,” Mone said, “I was running both businesses at once, calling into the fish auction, hanging up and then talking to a customer about a whole life policy.”

He still gets to look out on the water, but Mone will tell you he misses the fish business; he misses the whole scene. He misses Jerry McCarty who would be at the dock every tenth day at 7 am with a boatload of fish. “He was like clockwork,” Mone said.

He misses the camaraderie of his co-workers. Ollie Oliveira, who worked as a foreman with Mone for years said, “We were a bunch of rowdy young guys, and we were no strangers to the Ritz. Sometimes we didn’t change our clothes for days and they’d complain about the way we smelled — we just told them we smelled like money.”

Mone still has lunch with Trip Barnes, but he misses working with him. “Trip was a good artist and one time he was making a pitch for our business and he comes in with this presentation he drew up — the trucks were all bright and shiny, and all the drivers had white uniforms and bow ties.” Mone just laughs.

In a strange way he even misses the people coming down to the Co-op to try to score some free fish. “We used to call them seagulls,” Mone said.

But the Vineyard Co-op is gone now. Not only did it go out of business, a couple of years ago the old building on Packer’s dock was razed before it fell into the sea.

Gone but not forgotten.

Geoff Currier is an associate editor at the MV Times and frequent contributor to Edible Vineyard.

Wonderful story, Geoff, about a couple of true Vineyard characters, who still have twinkles in their eyes. So glad I was lucky enough to be here back in those days, to hear a few of those stories first-hand. Bless Bob and Trip — someone should write a book!