Cookbooks are a kind of history of the world told through our taste buds. The ones that sit on our bookshelves tell a story about our relationship to food and cooking — a story that is mostly under the radar, due to the ephemeral nature of a meal, and the fact that eating is just a backdrop for living life.

This winter I took Susan Klein’s “Pinch o’ This — Dash o’ That” family cookbook-making class because I’d been wanting to pass some recipes on to my two kids. Susan is a storyteller, author, editor, and teacher whose cookbook class was born out of her memoir workshops, because so many memories involved food.

A family cookbook can be a collection of recipes that are family favorites, or they might have some personal meaning beyond the list of ingredients. You might include a recipe written on a scrap of paper because the handwriting brings back memories of your long-departed relative. The cookbook can include photos and anecdotes about a dish, or someone who taught you to cook. It can be about the way you eat now, but it can also preserve family food history.

One of my favorite meals growing up was a savory bread pudding made with pieces of white Bunny bread alternately layered with Velveeta cheese, with an egg and milk mixture poured over it all, baked in the oven. At this particular point in my life, there isn’t a single one of those ingredients I eat, but I included it in the cookbook for its historical value, because it was what I loved as a kid, and what we ate a lot in the 1950s and ’60s. Susan’s kind of cookbook is like a memoir of that aspect of our lives that touches all parts and illuminates the whole: the food we make and eat.

It can be hard to remember what we ate long ago; even favorite dishes can fade into the daily life of the past. Susan used word prompts, and we’d write associated memories or thoughts, words like: wooden spoon, fried clams, Agricultural Fair, burned toast, and iceberg lettuce. That last one reminded me of the salads my mother sometimes made with only iceberg lettuce. She called it honeymoon salad, as in “lettuce alone.” At the cookbook class I learned there was another part — “lettuce alone with no dressing.” I guess the second part was too risqué for our young Episcopalian ears.

Memories can be attached to a particular dish, or place where you ate it. Including stories in the cookbook can illuminate a list of ingredients and give it flavor. Our memories helped us see what the cookbook could be. As Susan says, “Not only do you realize you have recipes to share, but the context of the recipes makes you realize how valuable they are.”

Delving into my food history made me remember long-ago memories like my early efforts at cooking — pancakes, muffins, and brownies, and favorite foods like butterscotch pudding, and pigs-in-a-blanket (sausages baked in a rolled-up biscuit) that we used to take for lunch at the ski slopes. I remembered the foods I loved (any pudding) and ones I couldn’t stand (scrambled eggs in the morning), and special foods we had for holidays, like hot cross buns at Lent and ham baked with pineapple rings on Easter.

Susan got us thinking about the life lessons taught, consciously or not, in the kitchens of our youth. For many of us growing up, it was about not wasting anything, and making do with what we had. My mother grew up during the Depression, and for the rest of her life, she always saved string, bags, and rubber bands. Someone in the class remembered finding jars and jars of peach pits in an old house she’d recently bought. Evidently the government had a campaign to get people to save them to make charcoal for gas mask filters in WWI.

Food never went to waste in our house. When I was growing up, there was a rule that we had to try some of whatever was served, as well as clean our plates — “Think of the starving Armenians!” But we were allowed to have one “favorite dislike.” For a while we lived on a farm in Winchendon, and one year a neighbor brought over some hog’s head cheese (actually made from the pig’s head, with the parts visible). It instantly became all of us kids’ favorite dislike, and was for many years, even after we moved to the suburbs of Detroit where they’d probably never heard of hog’s head cheese.

My mother served dessert with every dinner, usually something she’d made like jello or tapioca with a dab of jam, or occasionally something special like pineapple upside-down cake, chocolate wafer icebox cake, or exotic floating islands (meringue islands in a sea of custard). The few times she didn’t have anything for dessert, she would offer us mincemeat pie. We kids would all groan and decline. She didn’t actually have any mincemeat pie, and it was kind of a joke, but by offering she could feel like she’d fulfilled her duty and her mission, preparing three meals a day for her family of eight.

Making a family cookbook turns out to be more of a big deal than you might expect if you think you’re only going to put together a few recipes for posterity. For example, there’s the proofing. Susan told us that if you want to pass something on to future generations, you have to be specific but keep it simple, list the ingredients in the order they’re handled, and include concrete measurements and directions. If you’ve made something for 30 years but you make it slightly differently every time, you need to create a recipe for it and proof it.

For the proofing, it’s helpful to have another person write down the way you’re putting together the ingredients as you make the dish. If you’re used to adding ingredients intuitively, you can first measure out a set amount of each ingredient separately, then add as much as you want. At the end of the preparation, you can measure what’s left in order to know how much you used. Susan also suggested being consistent with amount abbreviations, and listing each ingredient in the instructions to make sure they’re all included in the mixing.

After you gather the recipes, photos, and other memorabilia, and edit the anecdotes and stories, the challenge is how to organize it all and actually put the book together. An eight-week class was not enough time, but as Susan said, “It does whet your appetite for the possibilities.” It’s not something I would have gotten to on my own, but I think I have the wherewithal to finish it within my lifetime.

In Susan’s last class, we each shared our passion around food and cooking. The kitchen has been a kind of laboratory for many of us, a place to experiment with combinations of foods and flavors, with no dire consequences for poor choices or failed experiments. I love the sense of possibility in creating a new dish or changing a recipe in order to use an ingredient I have or not use one I don’t have, trying an herb or spice in a new way.

Cooking always felt tedious when people expected it of me, and I wasn’t even all that interested in food and eating when I was younger. Over the years of growing, gathering, and cooking meals for my family, my kitchen has become one of my favorite places for creative expression. When the vegetables are fresh and in season, they become beautiful raw materials to play with. I’ve come to enjoy eating and thinking about food, too. Making the cookbook made me realize what a long journey I’ve been on, right here in the same kitchen I’ve cooked in for 45 years.

Sesame Seaweed Crunch

From Patrie Grace

¼ cup vegetable oil ½ cup maple syrup 1 tsp. shoyu pinch of cayenne (optional) 1 cup sliced almonds 1 cup sesame seeds 4 sheets nori cut in small pieces

Bring oil, syrup, and shoyu (and opt. cayenne) to a boil and simmer for a few minutes.

Add the almonds and stir.

Add the sesame seeds and stir, then add the nori.

Spread the mixture on a parchment lined (or oiled) baking sheet. Bake at 350º for 10 to 20 minutes until the edges brown.

Optional: You can replace some of the sesame seeds with sunflower or pumpkin seeds.

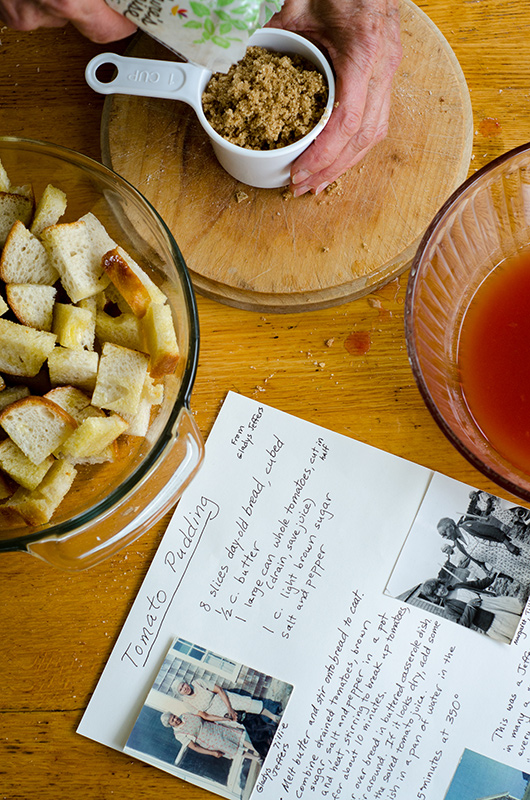

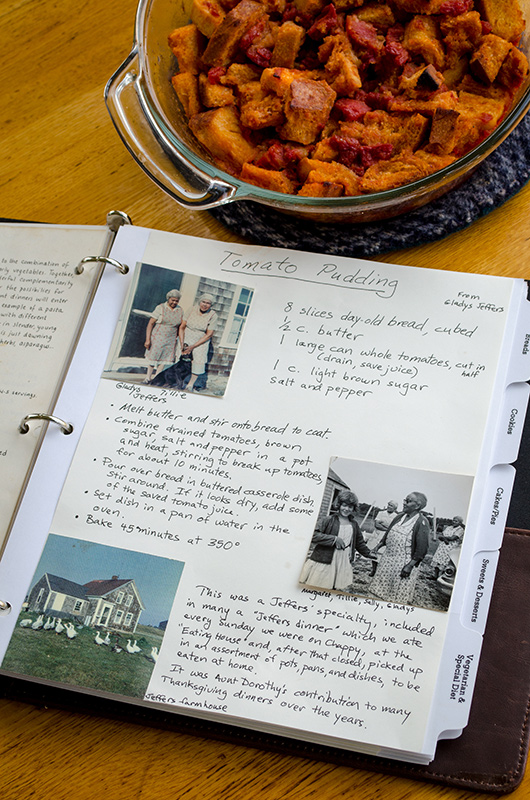

Tomato Pudding

From Gladys Jeffers

½ cup butter 8 slices day-old bread, cubed 1 large (28 oz.) can whole tomatoes (drain, save juice) 1 cup light brown sugar salt and pepper

Melt the butter and stir onto the bread cubes to coat, in a buttered casserole dish.

Combine the drained tomatoes, brown sugar, salt and pepper in a pot and heat about 10 minutes, stirring to break up the tomatoes.

Pour the mixture over the bread cubes. Stir, and if the mixture looks too dry, add some of the saved tomato juice.

Set the dish in a pan of water in the oven and bake at 350º for about 45 minutes.

Margaret Knight is a writer who lives on Chappaquiddick. She contributes regularly to The Local, The

MV Times, and MV Arts & Ideas Magazine.