“One night Butchie Lawry called me and asked me to go over to the Trade Wind airport in Oak Bluffs and change the lightbulb in the phone booth,” said Dick Carlson, a fish spotter from back in the 60s. “The pilots used the phone booth as an aiming point to find the runway,” Carlson said, which I thought seems to give new meaning to the phrase, “flying by the seat of your pants.”

Fish spotters flew in conjunction with fishing boats, spotting swordfish from the air and directing the boats to the fish so they could harpoon them.

It was a band of pilots from the Cape and Islands, Plymouth, and parts of Rhode Island who were collectively known as the “Georges Bank Airforce” because they spotted for boats on Georges Bank, a prolific fishing ground off the coast of Nova Scotia — at times there might be 20 or 30 planes hovering over the fleet. And if you think this sounds like a dangerous occupation, you’re right.

Edward (Spider) Andresen, who spent five years as a wheelman on a swordfishing boat back in the 70s, said, “It was a crazy thing to do, flying out 200 miles in a light plane over that kind of water is totally insane, and if you do it long enough eventually you’re going to die, no question about it.”

Louie Larsen, who grew up fishing on his father’s boat, the Mary Elizabeth, told me that one relatively calm and smooth afternoon, he watched as a fish spotting plane took a tight turn and stalled out and ditched not that far from his boat. “The plane sank to the bottom and the only sign of the plane was a pack of cigarettes that floated to the surface,” Larsen said.

Jack Mayhew, who fish spotted for many years in the 70s and 80s, said that one day he heard a distress call on the radio coming from Jonathan Mayhew, a fisherman and pilot from Menemsha who was fish spotting for his boat the Quitsa Strider when he developed engine problems and ditched his plane in shark-infested waters. Fortunately there was a boat nearby and he was able to swim — very quickly — to safety.

The risks were high but so were the rewards. Fish spotters could work in various arrangements with the fishing boats. Some fish spotter’s planes were owned by the fishing boats, others were owned by the individual pilots or owners who rented their planes to the pilots and were paid by the fishing boats according to the amount of fish they landed. Jack Mayhew said that he would generally make between $400 and $800 a day, which went a long way in 1980 dollars.

Fish spotting seemed to attract certain larger-than-life, swashbuckling types and after listening to some of the stories Dick Carlson told me, I said, “You guys were a bunch of cowboys out there, weren’t you.”

Carlson told me about coming up behind a pilot who was sitting out on the wheel of the plane to cool off, with no one else in the plane. “This kind of stuff happened all the time,” Carlson said. ”One time I saw a plane come up behind another and touch his wheels on the roof of the other plane.”

And closer to home, many of the spotters would often use their planes to touch down in the most improbable places. A group of pilots might fly up-Island and land in a field for a cookout. The Malley brothers, Ted and Tim, two legendary fish spotters, would land out at Nomans Land, an island off the coast of Gay Head which occassionally was used by the Navy as a bomb site.

Carlson tells the story of one night when Butchie Lawry was at the Ritz bar in Oak Bluffs and decided to give his drinking companion a ride home — in his plane — landing on Lobsterville Road in Chilmark, and taxiing up to his friend’s house.

Back in the 40s and 50s the swordfish were plentiful off the coast of Nomans Land and fishermen would just climb the mast of their boat to spot the fish, sunning on the surface. But it was just a matter of time before they began spotting with planes and the area became overfished. That’s what prompted the sword fishermen to head up to Georges Bank.

The fishing was good up there, but flying out 200 miles and back presented a new set of challenges. Jack Mayhew said that not all pilots liked flying over water; “But as fish spotters, we were more nervous flying over land because we had 30-gallon fuel tanks on the tips of our wings, and a 90-gallon belly tank under our seat, so if we ever ditched in the woods it would literally be like sitting on a powder keg. We felt safer over the water.”

In a personal journal Jack Mayhew shared with me, it became apparent that flying close to the water could also have its drawbacks.

“Once when I was flying back about 50 feet off the surface of the water,” Mayhew wrote, “I noticed some small whales that were surfacing and spouting sizable spouts, which, before I could react, I flew right through. This resulted in a very messy windshield, which required me to pull up a bit, and boy, did it smell bad! I had always heard that a whale spout smelled of rotten fish, and I can personally attest that it is true! “

Mayhew said that planes on the Vineyard flew out of both the main airport and out off a little grass runway at Trade Wind airport in Oak Bluffs.

“On a typical day,” he said, “we’d take off at 6 in the morning, get out to Georges around 9 am, fish until 5, and get home around 9 or 9:30 pm. There was camaraderie among the pilots, and sometimes we put on a little airshow for the boats before heading home.

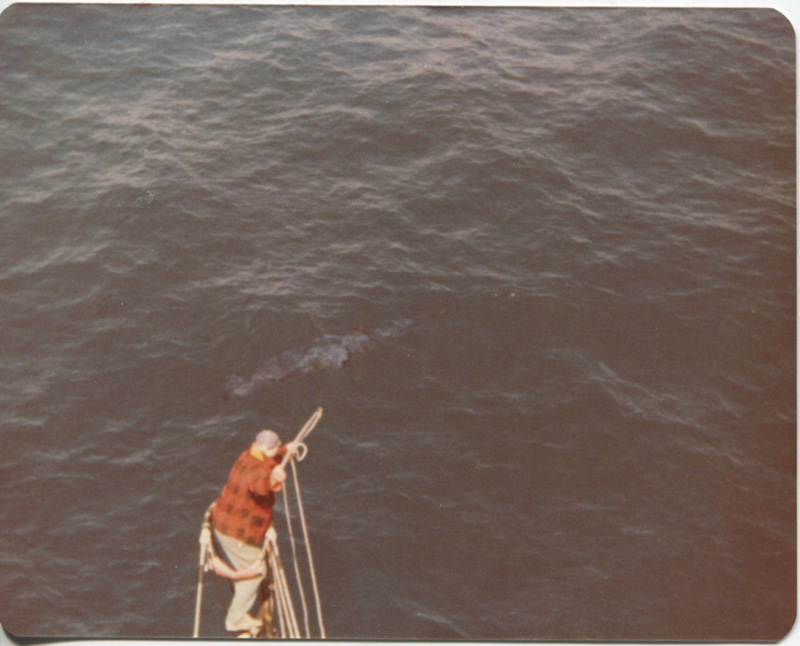

“Out at Georges, the drill was I’d fly over the boat in a racetrack pattern,” he said, “and when we’d spot a fish, sometimes we’d mark it with a green dye marker and then we would guide the boat to the fish over the radio, making sure the harpooner would be ‘down sun,’ or not looking into the sun.”

“The boat and the plane,” Larsen said, “would try to find an edge where water from two different temperatures would come together and it would attract fish. The water gets agitated and on a calm day, you can literally see it shake.”

Spider Andresen said that there weren’t just planes and trawlers out at Georges Banks, there could be up to 15 or 20 Russian factory ships out there as well, using a technique called long-lining that hung thousands of hooks off of a long line dragged behind the boat.

Andresen added that he would often socialize with the Russians. “We’d go up alongside and I introduced them to Budweiser,” he said, “and it was right about the time they introduced pop-tops, which the Russians had never seen before, and they thought that the pop-top cans were grenades, perhaps because Andresen shook a can up so it exploded on the deck. But even then, in the midst of the Cold War, they all had a good laugh.”

The 70s and 80s were heady times out at Georges Bank, but you won’t see the Georges Bank Airforce out there today. “Flying with fish spotters just became too expensive,” Louie Larsen said. Between the increasing cost of gear and fuel and maintaining a plane, it just became too expensive for boats to make money using spotters. “There are still swordfish out there, but today all the fishing is done by long-liners and gill-netters.”

Spotter planes are still used for tuna boats, which fish closer to shore, and the Japanese sushi market has made fishing for tuna extremely lucrative. But the days of those magnificent men and their flying machines heading out to Georges Bank to do battle with swordfish are pretty much a thing of the past. And what a past that was.